i.

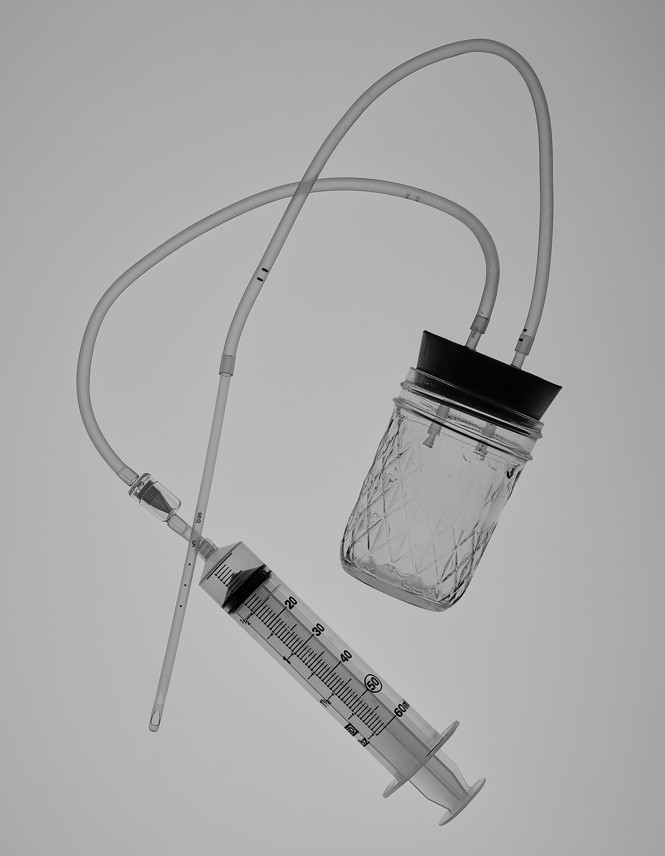

One bright afternoon in early January, on a beach in Southern California, a young woman spread what looked like a very strange picnic across an orange polka-dot towel: A mason jar. A rubber stopper with two holes. A syringe without a needle. A coil of aquarium tubing and a one-way valve. A plastic speculum. Several individually wrapped sterile cannulas—thin tubes designed to be inserted into the body—which resembled long soda straws. And, finally, a three-dimensional scale model of the female reproductive system.

The two of us were sitting on the sand. The woman, whom I’ll call Ellie, had suggested that we meet at the beach; she had recently recovered from COVID-19, and proposed the open-air setting for my safety. She also didn’t want to risk revealing where she lives—and asked me to withhold her name—because of concerns about harassment or violence from anti-abortion extremists.

Ellie snugged the rubber stopper into the mason jar. She snipped the aquarium tubing into a pair of foot-long segments and attached the valve to the syringe’s plastic tip. In less than 10 minutes, Ellie had finished the project: a simple abortion device. It looked like a cross between an at-home beer-brewing kit and a seventh-grade science experiment.

The two segments of tubing protruded from the holes in the stopper. One was connected to a cannula, the other to the syringe. Holding the anatomical model, Ellie traced a path with the tip of the cannula into the vagina and through the cervix, positioning it to suction out the contents of the uterus. Next, to show more clearly how the suction process works, she placed the cannula into her coffee. When she drew back the plunger on the syringe, dark fluid coursed through the aquarium tubing and into the mason jar, collecting slowly within the diamond-patterned glass.

I had read about such devices before. But watching the scene on the beach towel brought history into focus with startling clarity: Women did this the last time abortion was illegal.

Ellie didn’t invent this device. That distinction goes to Lorraine Rothman, an Orange County public-school teacher and activist. In 1971, members of her feminist self-help group had been familiarizing themselves with the work of an illegal abortion clinic in Santa Monica. The owner, a psychologist named Harvey Karman, had designed a slender, flexible straw—now known as a Karman cannula, and a standard piece of medical equipment—which he used to draw the contents of a uterus into a large syringe. Karman’s method took only a few minutes and had been nicknamed a “lunch-hour abortion” because patients could return to regular activities afterward. It was less invasive than dilation and curettage, a procedure that uses a surgical instrument to scrape the uterine walls.

Two years before the Supreme Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade changed the legal landscape for abortion in the United States, Rothman was developing her own version of Karman’s apparatus, rummaging around aquarium stores and chemistry labs for parts. She added a bypass valve to prevent air from accidentally being pumped back into the uterus, and a mason jar to increase the holding capacity. The result was an abortion device that was easy to make and suitable for ending pregnancies during most of the first trimester.

For purposes of plausible deniability, Rothman promoted the device as a tool for what she referred to as “menstrual extraction”: a technique a woman could use to pass her entire period at once, rather than over several days. In October 1971, she embarked on a Greyhound-bus tour with a fellow activist, Carol Downer, to spread the word. In six weeks, they visited 23 cities, traveling from Los Angeles to Manhattan and calling themselves the West Coast Sisters. Soon women all over the country were making the device, which Rothman and Downer had called a Del-Em. (When I met Downer, now 88, earlier this year, I asked her about the meaning of the name; she said it was an “inside thing” and “not to be shared.”)

One might have expected the Del-Em to have disappeared after Roe affirmed the constitutional right to an abortion everywhere in America. Yet the Del-Em remained quietly in use here and there, conveyed from one generation to the next. This was in part because of continued fears that abortion rights would again be curtailed—an event that may now be imminent if the Supreme Court upholds statewide bans. But it was also because of a desire among some women to maintain control over their bodies, without oversight from the medical profession, regardless of Roe’s status.

Activists are still tinkering with Rothman’s design. One added a second valve. Another upgraded the suction using a penis pump (a vacuum device used to stimulate an erection), explaining, “It’s like going from a pogo stick to a Lamborghini.” An American midwife living in Canada told me about repurposing an automotive brake-bleeding kit: “You just add a cannula onto the end.” She estimated that she had performed hundreds of abortions, using the Del-Em but also other methods, including medical-grade manual vacuum-aspiration kits and pharmaceuticals. The midwife is part of a network of self-described “community providers”—a term for people who perform abortions and offer other reproductive-health-care services outside the medical system. Before the coronavirus pandemic, she traveled and taught in-person workshops throughout the U.S. and Canada. She now teaches online. Ellie learned to build a Del-Em in one of her classes.

For Ellie, the Del-Em was more symbolic than pragmatic—an amulet from the past to carry into an uncertain future. After all, pharmaceuticals can now be used to end pregnancies in the first trimester, when more than 90 percent of legal abortions occur. (Almost 99 percent of abortions occur within the first 20 weeks.) There are also modern, mass-produced manual vacuum-aspiration devices for doing what the Del-Em does. Community providers have talked about stockpiling such supplies in case Roe falls. Ellie has coined a term for people who share that outlook: “vaginal preppers.”

Given the uncertainties, she suggested, it couldn’t hurt to have a do-it-yourself tool like the Del-Em. “Just knowing the people who came before you had other ways of managing these things, not necessarily through a doctor or condoned by a government—there’s something really powerful in that,” she said.

As Ellie packed her supplies back into a tote bag, she told me to take the Del-Em. She gave me the speculum, too.

ii.

There is a lot of talk about prepping these days. Roe v. Wade could well be further weakened or overturned by late June, when the Supreme Court is expected to hand down a decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. At issue is a Mississippi law banning nearly all abortions past 15 weeks of pregnancy. This is a direct challenge to both Roe and the Court’s follow-on decision, nearly two decades later, in Planned Parenthood v. Casey. In these two decisions, the Court has held that states can ban abortion (except when the mother’s health or life is threatened) only past the point of fetal viability, which Casey found to be when a woman is roughly 23 to 24 weeks pregnant. Prior to that point, the Court’s holdings permit states to impose limited restrictions on abortion, so long as they don’t pose an “undue burden” on a woman’s right to an abortion. The Court now has a 6–3 conservative majority. By upholding the Mississippi ban, it would, in essence, nullify Roe’s recognition of the constitutional right to an abortion prior to viability. According to a 2021 Gallup poll, fewer than one in three Americans supports that outcome. The legality of abortion would largely be left to the states. Twelve states have “trigger bans” on the books—laws that will take effect the moment Roe is overturned. More than half of all states are certain or likely to attempt to ban abortion if the Supreme Court provides legal space to do so, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a pro-abortion-rights research organization.

For many Americans, Roe already feels meaningless. Nearly 90 percent of U.S. counties lack a clinic that offers abortions. States have passed more than 1,300 restrictions on abortion since it was made a constitutional right; for people struggling to get by, those restrictions can be insurmountable. Obtaining an abortion often means traveling long distances, which also means finding money for transportation, lodging, and child care, not to mention taking time off from work. In some states, people may reach a clinic only to learn that they are legally required to make two visits—one for counseling, the second for the abortion—with a mandatory waiting period of up to three days in between. The cost of an in-clinic abortion ranges from about $500 in the first trimester to more than $1,000 if the pregnancy is further along; that expense is ineligible for federal funding under a long-standing restriction called the Hyde Amendment, which makes abortions inaccessible for many low-income people.

A sprawling grassroots infrastructure has already grown in the cracks created by such challenges, even with Roe still the law of the land. More than 90 local organizations known as abortion funds raise money to pay for procedures and related expenses. Practical-support groups offer rides to medical facilities, along with housing, child care, and translation services. Clinic escorts guide patients past throngs of angry protesters. Doctors and other abortion providers travel hundreds of miles to work in underserved areas that are openly hostile to abortion.

This improvised safety net doesn’t catch everyone, though. Below the grass roots is the underground: a small network of community providers who connect with abortion seekers by word of mouth. This network, too, is growing. Its ranks include midwives, herbalists, doulas, and educators. When necessary, they are often willing to work around the law.

Even before the pandemic, with state restrictions mounting, the grass roots and the underground struggled to meet the demand for help. Then, as the coronavirus was first surging, a dozen states—most of them in the South, but also including Alaska, Iowa, and Ohio—moved to suspend nearly all access to abortion, describing it as a nonessential procedure. A handful of those efforts were temporarily successful, creating what felt to some like a dress rehearsal for the end of Roe. That feeling returned last fall when Texas used a creative legal strategy to ban most abortions after roughly six weeks’ gestation. Legal challenges to the law have so far failed.

The impact of the Texas law was immediate. Neighboring states experienced a swell of people seeking help, creating bottlenecks and forcing local patients to go out of state themselves in a secondary wave of migration. A term gained currency: “abortion refugees.”

Ellie told me she was disgusted by the developments in Texas. “Our reproductive rights are not given to us by the government,” she said. “They’re not given to us by anyone. We inherently have them.” Her belief in that sort of independence was formed long before the current debate; her family, she explained, was always interested in alternative medicine and, by age 7 or 8, she wanted to become a midwife. As a preteen, she read a novel called The Red Tent, set in biblical times, whose title refers to a place where women find refuge during menstruation and childbirth. In high school, classmates brought her their awkward questions about sex. After college, Ellie attended a retreat for sex educators that rekindled her old interests. She took jobs providing midwives and doulas with logistical support and eventually started a business in reproductive health—a red tent of her own.

iii.

It seems hard to imagine now, but America was not always so sharply divided over abortion. In the early decades of American independence, the states drew guidance from traditional British common law, which did not recognize the existence of a fetus until the “quickening”: the moment a woman felt the fetus move, usually during the second trimester. Before that, even if pregnancy was suspected, there was no way to confirm it. Women could legally seek relief from what doctors characterized as an “obstructed menses,” soliciting treatments from midwives or home-health manuals and in many cases making use of herbs that had been employed since antiquity (and that are sometimes used today).

[Read: Bringing down the flowers: The controversial history of abortion]

Through the first third of the 19th century, as the historian James Mohr has noted, abortion was widely seen as the last resort of women desperate to avoid the disgrace of an illegitimate child. Over the next few decades, the incidence of abortion rose. Mohr explains that the impetus came largely from “white, married, Protestant, native-born women of the middle and upper classes who either wished to delay their childbearing or already had all the children they wanted.” By mid-century, newspapers were full of advertisements for patent medicines such as Dr. Vandenburgh’s Female Renovating Pills and Madame Drunette’s Lunar Pills, which claimed—with a knowing arch of the eyebrow—to restore menstrual cycles. Some of the commercial preparations were dangerous; the first abortion statutes, passed in the 1820s and ’30s, were mostly poison-control measures aimed at regulating these products.

The effort to regulate abortion more explicitly, which began some years later, was less civic-minded. At the time, American physicians were working to organize and consolidate their profession. After forming the American Medical Association, in 1847, they began lobbying against abortion—ostensibly on moral grounds but also in part to neutralize some of the competition from midwives and homeopaths. Within a generation, every state had laws criminalizing the practice, pushing it into a netherworld and inviting dangerous procedures. In 1930, some 2,700 women died from abortions, according to the Guttmacher Institute. While some providers—including physicians—managed to offer safe, sometimes clandestine care, many women resorted to shady practitioners or self-managed abortions. By 1965, fatalities caused by illegal abortions still accounted for nearly a fifth of maternal deaths.

As the women’s-rights movement gained momentum, doctors, lawyers, and public-health advocates began lobbying to reform abortion laws. Some activists, tired of waiting for change, took matters into their own hands. Underground abortion-referral services began to operate across the country. The Army of Three, a trio of California activists, traveled nationwide, holding workshops; they also distributed lists of well-vetted abortion providers in other countries. The Clergy Consultation Service—a group numbering 1,400, mainly Protestant ministers but also including rabbis and Catholic priests—connected countless women with abortion providers. Their work is a reminder that the abortion debate, often presented in stark terms of religious faith versus personal freedom, has always been one where people weigh competing values in complex ways.

[From the December 2019 issue: Caitlin Flanagan on the dishonesty of the abortion debate]

Women like Lorraine Rothman and Carol Downer, meanwhile, were spreading the news about the Del-Em; before Roe, menstrual-extraction groups were active all across the country. Such work was part of a larger mission that activists called self-help: teaching women how to take charge of their own reproductive health. In Chicago, volunteers with a group called the Jane Collective started out by referring patients to abortion providers, then learned how to perform the procedure themselves. The group performed about 12,000 abortions from 1969 to 1973.

American women weren’t alone in pushing back against abortion restrictions. In Brazil, where abortion has been a crime since the late 19th century, women found another way to resist. In the 1980s, they discovered an off-label use for a drug called misoprostol, sold under the brand name Cytotec, which was marketed for treating stomach ulcers. It had a potent side effect: heavy uterine contractions that could expel an early pregnancy. This discovery led to misoprostol’s adoption as an abortifacient by the medical community. In 2005, the World Health Organization added misoprostol to its list of essential medicines, along with another abortifacient, mifepristone, better known as RU-486. The drugs have become a major focus of the American abortion underground today.

iv.

One December afternoon on a Zoom call conducted from Cambridge, Massachusetts, a dozen participants tucked Skittles and M&M’s into their cheeks, then looked at one another awkwardly. I was among them. We had been told to position the Skittles and M&M’s with care: two on each side of the lower jaw, nestled into the buccal cavity, the pouch running along the gums. This is a method for taking misoprostol. Absorbing the drug in this manner—or alternatively, by means of vaginal insertion—means it bypasses the digestive system, going directly into the bloodstream. Chipmunk-faced, we awaited further instructions.

[Read: Women in the U.S. can now get safe abortions by mail]

“Keep them there for 30 minutes,” instructed Susan Yanow, a reproductive-rights advocate. “What we’re going to learn right now is that’s easier said than done—to not chew, to not swallow.” In real life, she added, the pills would melt even more slowly than the candies. And they would taste like cardboard.

The audience had logged on from eight states, as well as from Poland and Peru, to learn about ending pregnancies with legal drugs and without medical supervision. In other words: self-managed abortion by means of pharmaceuticals. “The knowledge you’re going to get today is very empowering,” Yanow told the group. “But the real power is in sharing it.” If Roe is overturned, she said, more people will need access to this information, and fast. Part of Yanow’s job is spreading the word. She is the spokesperson for SASS—Self-Managed Abortion; Safe and Supported—a project of the global advocacy group Women Help Women, which had developed the day’s curriculum. The class was designed to self-replicate with a model called “train the trainer,” turning students into future teachers.

Abortion pills—mifepristone and misoprostol, colloquially called “mife” (pronounced “miffy”) and “miso”—are remarkably effective and medically safer than acetaminophen and Viagra. They’re FDA-approved for ending pregnancies up to 10 weeks’ gestation. The WHO has protocols for using them to end pregnancies up to 12 weeks’ gestation, and even later. (Taking them further along, however, can raise the risk of complications.) Misoprostol is often used on its own to induce an abortion. But the most effective protocol calls for both drugs in sequence, and with time in between—first mifepristone, then misoprostol. The combination is available online, for prices that typically range from $150 to as much as $600, depending on one’s state and insurance. In many states, it can legally be prescribed by telemedicine and delivered by mail.

Some reproductive-rights activists point to pharmaceuticals as the best fallback plan for a post-Roe era. Ending a pregnancy with pills, also known as medication abortion, already accounts for more than half of all abortions in the U.S. But most American adults don’t even know the option exists. Only about one in five has heard of medication abortion, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation survey published in 2020. Among adult women of reproductive age, it’s about one in three.

That knowledge gap can have serious consequences. Laurie Bertram Roberts is the executive director of the Alabama-based Yellowhammer Fund, which offers financial support for abortion seekers. In recent years, she told me, she has encountered or heard about situations in which pregnant women drink bleach or turpentine, “jab a coat hanger up into themselves,” or “ask their boyfriends to beat them up.” She believes that if more people knew about abortion pills—particularly women of color and the poor, who will be disproportionately affected by a Roe reversal—they would be far safer. “To me, as a Black person, it just makes sense,” she said.

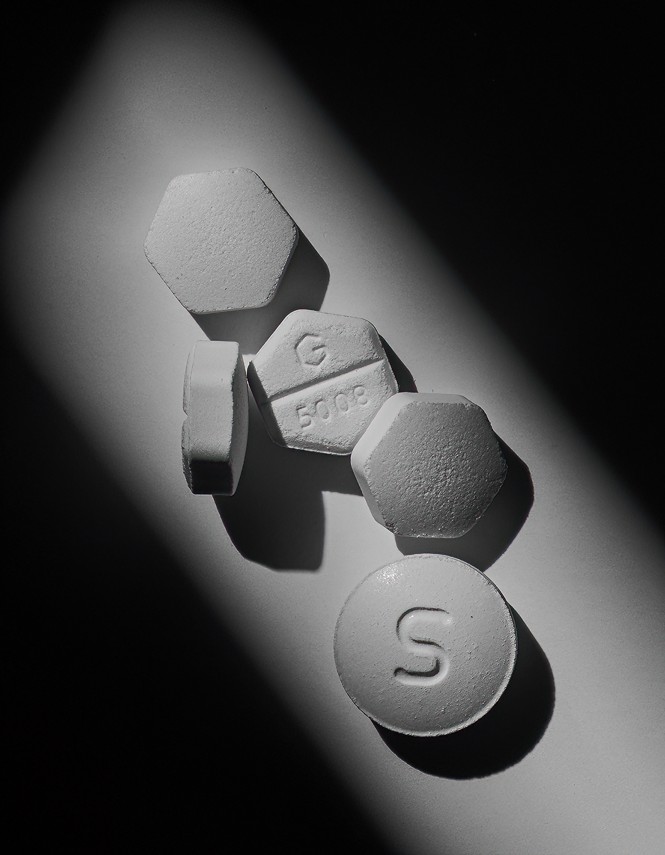

the pharmaceuticals used in medication abortion (Hannah Whitaker for The Atlantic)

Pills are not a one-size-fits-all solution—no drug or medical procedure ever is. Any form of intervention requires care and common sense, and attention to other health issues. People with certain medical conditions, including bleeding disorders and adrenal failure, are unable to use abortion pills. And not everyone reacts to the medication the same way. In most cases, the contents of the uterus are expelled within four hours, and almost certainly within two days, but the process can take as long as a week. (In contrast, vacuum-aspiration methods are also used for terminating early pregnancies, but typically take less than 30 minutes.)

Laws governing access to the medications are in constant flux and differ wildly around the country; erecting roadblocks to abortion is a clear motivation behind much of the legislation. Thus, 19 states bar the use of telehealth for medication abortion or require patients to consume mifepristone in the physical presence of a clinician; some do both. That eliminates the cheaper and more convenient option: a consultation online or by phone, then receiving pharmaceuticals in the mail. In Texas, patients seeking a medication abortion must make three in-person visits: one for counseling, another to receive the pills, and a third for a medical check afterward.

Self-managed abortion is currently banned outright in three states. Its status is legally murky in many others. At the start of her three-hour class, Yanow opened a PowerPoint presentation. She showed us a map of the U.S. with 22 states shaded in orange. In those places, Yanow said, self-managed abortion had led to people being investigated. Some were charged with felonies under laws that were not actually intended to target abortion, including murder in Georgia and abuse of a corpse in Arkansas. In Indiana, a woman named Purvi Patel was convicted of feticide and given a 20-year sentence. The conviction was later overturned, but only after Patel had already served three years in prison. Yanow drove the message home: Anyone who helped those people could have been charged, too, as accessories to a crime.

If it were possible to feel the air go out of a Zoom room, we would have felt it then. But, Yanow continued, there was a simple way to stay safe legally. That was to only share information, rather than give explicit advice, encouragement, or assistance.

Yanow described the availability of misoprostol and mifepristone. Mife is tightly regulated and can cost more than $100 a pill. Miso is much cheaper and easier to find. It is used to treat stomach ulcers in humans as well as in cats, dogs, and horses. Pharmacies in Mexico sell misoprostol under its Cytotec brand name. The pills come in blue-and-white boxes with fuchsia accents and have a shelf life of about two years. “The last time I was in Nuevo Progreso, a tiny border town, they were stacked up on the counter like chocolate bars would be here,” Yanow recalled. “As if for an impulse buy.”

Yanow matter-of-factly described what people taking the two-drug combination can expect. The regimen starts with mife, a progesterone blocker that stops the pregnancy from growing. It continues one or two days later with miso, which makes the uterus contract and expel gestational tissue. The experience is like having a spontaneous miscarriage. There can be heavy cramping and bleeding, with the possibility of passing clots up to the size of a lemon. The possible side effects include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and fatigue. Complications are very rare, and generally resemble those associated with a miscarriage; there is a small risk of hemorrhage or retaining tissue (which may have to be removed by a medical provider). Bleeding through more than two maxi pads in two hours is considered excessive, warranting medical attention. For the unprepared, a hospital visit could mean legal complications, too.

Yanow told the story of a woman named Jennifer Whalen, in Pennsylvania, who bought mife and miso online for her pregnant 16-year-old daughter. After the teenager took the pills, her miscarriage began. She became frightened when stomach pains hit, so Whalen drove her to an emergency room and told doctors about the pills. The daughter was fine, but Whalen was charged and pleaded guilty to offering medical advice without a license. She was given a jail sentence of nine to 18 months.

People in similar situations need to know how to present themselves to doctors, Yanow said. “They can say they’re having a miscarriage, or they’re bleeding and they don’t know why,” she explained. According to Paul Blumenthal, a professor emeritus of obstetrics and gynecology at Stanford University, it is safe for patients to self-report this way; a medication abortion is clinically indistinguishable from a spontaneous miscarriage and treated in the same fashion.

Later in the class, it was time to role-play. Yanow gave each of us a part. Some of us were six weeks pregnant and seeking abortion pills. Others had information to share and a mission: Pass it along. The goal was to avoid giving direct advice, because that could be construed as the unauthorized practice of medicine, a criminal offense. The key, Yanow said, was avoiding “that forbidden three-letter word: y-o-u.”

v.

No matter how the word is passed, more autonomy is coming, at least eventually—both in places that attempt outright bans and also where abortion remains legal. The weakening or overturning of Roe would of course have an impact, and it would be significant. Statewide bans on abortion would cause a rise in maternal deaths—of women with complicating health issues and of women who resort to dangerous methods. Maternal deaths will also rise because women who want an abortion can’t get one—childbirth is far riskier than ending a pregnancy.

But other forces are also at play. A post-Roe world will not resemble a pre-Roe world. Women already have different options. In Blumenthal’s view, the future doesn’t lie in Planned Parenthood (which in addition to education and advocacy offers abortion services through a network of clinics). “I think the future lies in more self-managed care and alternative distribution schemes,” he told me. Pharmaceuticals are a big part of that future—the work-around of first resort and one that’s hard for authorities to stop. Blumenthal’s confidence in the safety of medication abortion, including when it is self-managed, is the medical consensus, supported by the WHO, the FDA, and numerous studies.

In circumstances where pharmaceuticals may not be appropriate, he believes that laypeople can be instructed to wield manual vacuum-aspiration devices, including the Del-Em, with little risk of infection. Technicians without medical degrees, he added, have been using such tools safely for decades in South and Southeast Asia. “This is not a complicated procedure,” Blumenthal said. Vacuum aspiration outside a clinical setting is not “self-managed” the way pills can be—it requires assistance. Although specific studies are few, they suggest that outcomes involving trained nonphysicians are comparable to those involving physicians (and in either case, the risks are very low).

Even clinical abortion providers who work directly with patients acknowledge that the future may involve them less. Asked about this, Danika Severino Wynn, the vice president of abortion access for Planned Parenthood, replied in a written statement: “Some people may choose to self-manage their abortion with pills, and this may become more common as laws increasingly restrict access to legal care. Planned Parenthood honors and respects this decision and will provide education, support, and any needed clinical care to anyone who seeks it—no matter what.”

Some patients can’t—or don’t want to—manage their own abortions. For them, and for those seeking the dilation-and-evacuation abortions that are most commonly used in the second trimester, the services provided by Planned Parenthood and independent clinics will remain necessary. But for a variety of reasons, including legal restrictions on abortion, the number of brick-and-mortar clinics has been dwindling for years.

Efforts to prepare for a post-Roe future have been undertaken in unexpected places. In 2020, a hackers’ convention called HOPE included talks on coding and digital privacy along with something quite different: A speaker using the alias Maggie Mayhem showed how to build and operate a Del-Em in a workshop titled “Hackers in a Post Roe v. Wade World.” In her presentation, Mayhem employed a demonstration method that has been used for training clinicians and medical residents: evacuating a papaya. (According to research published in the journal Family Medicine, “Papayas resemble the early pregnant uterus in size, shape, and consistency, and their softness makes them somewhat more realistic models than durable plastic devices.”)

In December, when the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Dobbs, post-Roe prepping intensified. Volunteers across the country handed out thousands of boxes labeled Abortion Pills. (Rather than actual medication, they contained cards with a link to shareabortionpill.info, a website that does what the name suggests.) The pro-pill message was amplified with posters, yard signs, stencils, a mural, a digital-billboard truck, and a plane towing a banner over Arizona. The campaign was run by Shout Your Abortion, a nonprofit that aims to destigmatize the procedure by helping people speak publicly about their experiences.

Whatever the laws may say, history has shown that women will continue to have abortions. The spread of pills and devices like the Del-Em—discreet, inexpensive, and fast—could, if nothing else, help ensure that abortions are done safely and, because of their accessibility, on average earlier in a pregnancy than is the norm today.

Even so, pill proselytizers and Del-Em makers are not the only ones prepping. A nonprofit called Abortion Delivered is planning to deploy mobile abortion vans. The first one was being readied when I spoke with a staff member at the organization who, like Ellie, did not wish to use her name. I’ll call her Angela. The van was being bulletproofed, Angela told me. It would then be retrofitted with an ultrasound machine and a gynecological-exam table, so a doctor with a manual vacuum-aspiration device could perform first-trimester abortions inside. Abortion Delivered, which originated in Minnesota, planned to dispatch the van—and a second one, stocked with abortion pills—to just outside the Texas border.

“They are small and inconspicuous,” Angela said. “Part of the appeal of it is that we can pass unnoticed and not draw attention.” She did worry about clinicians’ and patients’ safety along the edge of a heavily armed, anti-abortion state. Local FBI agents had been advising on security procedures, she said.

I asked Angela what Abortion Delivered would do with the vans if the Supreme Court weakened or overturned Roe. “Well, we’re going to need more,” she said. A cluster of nearby states—Wyoming, North and South Dakota, Nebraska—would likely also curtail abortion access. “We will just be driving up and down the borders,” she explained. “With four fleets, we think we could cover them.” She already has road experience, having delivered abortion pills throughout rural Minnesota in a rented Winnebago. “We would be in one town for 20 minutes,” Angela said, and then the Winnebago would move on. “And no one knew our route.” This may sound like the public-health version of Mad Max meets Station Eleven, but it’s easy to see how such a scene could become part of the future. Abortion providers have been traveling from state to state for decades—they used to be called “circuit riders”—to work at understaffed abortion clinics, often in hostile territory.

If the abortion deserts of the Midwest and the South become even more arid than they already are, people will take to the road in ever-greater numbers. Clinicians got a preview of the abortion diaspora after Texas—home to one in 10 reproductive-aged American women—passed its ban. According to a study published earlier this year, clinics as far as Maryland and Washington State saw a rise in patients from Texas. The resulting backlog also created longer wait times. Pregnancies progressed. Some patients who would have otherwise been eligible for abortion pills or manual vacuum aspiration ended up requiring second-trimester surgeries instead.

Other abortion seekers found themselves stuck in Texas. Some ended up having to give birth, unless they were among the lucky few to stumble on an underground provider network. One California activist described mailing misoprostol—something she’d never done before—after getting a panicked request from Texas. “A friend of a friend of a friend reached out and said, ‘There’s a 13-year-old girl who needs access, like, right now. And I know that the timing is bad, but can you help?’ ” Her package, which also included a greeting card, some coffee, and Naomi Alderman’s novel The Power, about women taking over the world, arrived the day the ban took effect.

vi.

More of America may soon look like Texas—but in a post-Roe world, states where abortion remains accessible could look quite different too. The new infrastructure being put into place extends beyond the grassroots efforts of American abortion activists. California and New York—the two states with the most abortion clinics—have been preparing for an influx of patients. “We’ll be a sanctuary,” California Governor Gavin Newsom stated in December. Planned Parenthood clinics in Orange and San Bernardino Counties are already staffing up, according to the Los Angeles Times. Political leaders pushed for public funds to cover the costs of low-income, out-of-state women visiting for abortions. In New York, Attorney General Letitia James proposed a similar fund to make the state a “safe haven.”

Activists in Mexico, whose Supreme Court decriminalized abortion last year, have been planning to help Americans with access. Some are already getting misoprostol into the U.S., by foot and by mail. Aid Access, an Austrian nonprofit, now offers “advance provision,” allowing Americans who aren’t pregnant to order mife and miso for possible future use. The organization serves all 50 states, including those with restrictions on medication abortion. The founder of Aid Access is Rebecca Gomperts, a physician who first gained prominence for creating the organization Women on Waves, which sailed to countries where abortion was illegal, picked up patients, then administered abortion pills in international waters. Similar methods—floating clinics in the Gulf of Mexico’s federal waters; a cruise ship turned clinic anchored outside U.S. jurisdiction—are on the minds of American activists.

In late January, I visited three women from a West Coast menstrual-extraction group founded in 2017 by a sex educator I’ll call Norah, who had organized it as a response to President Donald Trump’s election on an anti-Roe platform. The four of us sat in a backyard bungalow, eating cheese and crackers as a fireplace crackled on a wall-mounted television. The group members talked about abortion access—which they hoped to expand by teaching menstrual extraction to activists in heavily regulated states. They had already trained visitors from Kentucky and Texas and had plans to host someone from Ohio.

After talking for almost two hours, we filed into a bedroom for a demonstration. A woman I’ll call Kira attached a Del-Em to a pink Spectra S2 breast pump. Once switched on, the machine began to purr and click at regular intervals; it sounded like a robot snoring.

Norah, who was not pregnant but was menstruating, undressed from the waist down and lay on the bed. She expertly installed a speculum in her vaginal canal, creating a direct route to her cervix. Kira began to insert the cannula. “I’m at your os,” she said, referring to the cervical opening. “Is it okay to enter?”

“Go for it,” Norah said. The group chatted to pass the time—why do faxes still exist?—until blood appeared in the aquarium tube.

After 15 minutes of extraction, a small clot, nothing unusual, clogged the cannula. Because this was just a demonstration and Norah was getting crampy, they decided to stop. Kira removed the cannula and let the tube drain into the mason jar, where the contents settled: an inch of blood. And then it was over.

I thought back to an afternoon I’d spent interviewing Carol Downer, who toured the Del-Em across America with Lorraine Rothman more than 50 years ago. On her porch in a quiet Los Angeles suburb, we talked about what might happen if the constitutional right to abortion was lost. Downer was glad pharmaceuticals had been added to the feminist toolbox, she told me, though she was concerned about the government finding a way to take them out of women’s hands and she worried about people taking pills in isolation, without a context of friendly support. Downer still kept a Del-Em in her library, sitting on a table. She was confident the device would remain available. (“It’s a lot harder to ban mason jars,” she observed.) She reflected on the new underground that was growing, and the variety of tools it was employing: “We need all of these things,” she explained.

vii.

Efforts are expanding to provide the kind of friendly support spoken of by Downer. On a Saturday evening in early January, some 40 participants trickled into a conference room on Jitsi Meet, an encrypted, open-source Zoom alternative favored by the anti-surveillance set. We had been instructed beforehand: No real names. No audio, except for the presenters. No video. The screen filled up with blacked-out squares and aliases: Jolly Broccoli. Astronaut Witch. Blue Dinosaur. Tulip Jones. Adventurous Fern.

Zane (a pseudonym) was a volunteer with Autonomous Pelvic Care, an Appalachia-based reproductive-health organization that teaches courses for community-care providers on subjects such as self-managed abortion with pills, menstrual extraction, fertility tracking, and digital security. It had been a fraught week. Eight days earlier, on New Year’s Eve, an arsonist had burned down the Planned Parenthood office in Knoxville, Tennessee. Ever since, Zane told me, they’d been preparing to host this evening while fielding panicky messages from community members asking, “What do we do now?”

Tonight’s session featured four educators and was aimed at community providers and anyone else who might be supporting someone through a self-managed abortion. Zane started the session by talking through a protocol for mifepristone and misoprostol. One of the evening’s presenters, an herbalist and doula with Holistic Abortions, offered ways to ease the process—before, during, and after—with the goal of improving the whole abortion experience.

Next came a volunteer from Mountain Access Brigade, which runs a secure voice-and-text support line for abortion seekers in eastern Tennessee and Appalachia who need logistical, emotional, and financial assistance. She shared a website called Plan C, which includes a state-by-state directory for ordering pills online.

The last presenter was from If/When/How, a reproductive-justice legal-advocacy group that had recently announced a $2 million defense fund to cover bail, expert witnesses, and attorneys’ fees for people who get arrested after managing their own abortions. Prosecutors, she noted, have been known to repurpose obscure laws—including some from the 18th century—that were not meant to criminalize self-managed abortion.

Much of the material in this workshop and Susan Yanow’s session was new to me. But the tone felt familiar: Two years into the pandemic, we’ve all become public-health preppers. We’re more keenly attuned to threats and better stocked with the tools—hand sanitizer, antigen tests—to meet them.

No matter what happens to Roe, my own freedoms seemed unlikely to change much, at least for the foreseeable future; after all, I was living at the time in Los Angeles and make my permanent home in New York City. Even so, I decided to order some pills. I went online to Plan C and scrolled through the drop-down menu to California. There was a buffet of choices: Six telehealth providers, including Aid Access and start-ups called Hey Jane and Choix, offered mifepristone and misoprostol together beginning at $150.

For preppers—people who wouldn’t need the pills immediately—the best choice appeared to be ordering them from Aid Access, the only service offering advance provision. I placed my order on Saturday night, a few hours after the Autonomous Pelvic Care session wrapped up. I didn’t have to speak with anyone directly. An online questionnaire took less than 15 minutes and ended by asking the reason for my order, with a litany of mostly depressing options: Stigma. Cost. Having to deal with protesters. The need to keep my treatment a secret. Legal restrictions. Risk of abuse from my partner. The next day, my order was approved and I made an online payment of $150.

Four days later, a U.S. Postal Service package arrived. It came from an online pharmacy called Honeybee Health, just seven miles from where I was living. Inside, a plastic sleeve patterned with festive dots held the goods: a few leaflets, a box of mifepristone, and a teal bottle with hexagonal tablets inside. I tipped them into my palm and counted eight misoprostol pills. They looked utilitarian and chalky, nothing like M&M’s.

The instructions were printed on a double-sided flyer. A cartoon showed two pills tucked inside a cheek. Another showed a woman lying on her side, barefoot, eyes closed. Her arms were wrapped around her midsection. Her knees were drawn up to her chest. The caption said, “Expect bleeding.” Looking at the drawing made me feel queasy, even a bit afraid. I wanted to draw a friend next to her.

Instead, I rewrapped the package. Then I tucked it away, wondering if the contents would look any different in June.

This article appears in the May 2022 print edition with the headline “The Abortion Underground.”